AALT Home

Attorneys in Early Modern England and Wales

Litigiousness in Early Modern England

Causes of Litigiousness: New Territories subject to the Common Law

Conclusion: Two statutory actions increased the potential users of the common law: the statutes unifying England and Wales and the statute resuming liberties

Resumption of Liberties

Right in the midst of Henry VIII's Reformation, Parliament passed an act to resume certain liberties, effective in 1536 (Statute 27 Henry VIII, c. 24). Medieval England had been a patchwork quilt of jurisdictions. Some areas were high liberties in which the king's writ did not run. Other liberties had rights such as the franchise of return of writs (see Palmer, The County Courts of Medieval England, pp. 263-81) that interposed a layer of bureaucracy that could discourage people from using the court of common pleas. The statutory resumption of liberties was probably intended to disarm the monasteries of their role in governance preparatory to the dissolution. (See Palmer, Selling the Church, pp. 209-11.) At the same time, however, it regularized jurisdictions and included into the ambit of the common law areas that had always been subject only to local courts. For areas with only the franchise of return of writs, the statute meant that there were fewer impediments to litigation.

The effect on the volume of litigation in the court of common pleas would not have been instantaneous. Social customs change slowly when there is no dramatic impetus to change, but only the freedom to change. Local populations who were well accustomed to using local courts would have probably continued to do so for some time. Likewise, those populations had to have access to attorneys to use the court of common pleas. There were not many attorneys around even by the beginning of the reign of Elizabeth. (See Attorneys in Early Modern England and Wales.) Toward the end of the sixteenth century many more locally-based attorneys also functioned as attorneys of the court of common pleas. Those local populations who had been excluded from the common law or who had encountered the disincentive of the franchise of return of writs were now included. This effect was a growth in the population who would use the law, but not because of a demographic increase. The reason for this increase also predates the 1560-1640 period: the change was the longer term effect of this part of the reforms of Henry VIII.

Precisely how much new litigation the resumption of liberties in fact produced is probably not capable of proof. As shown later also for Wales, however, new processes made it possible for plaintiffs to use the court of common pleas to sue residents of Cheshire, Durham, and the Duchy of Lancashire; the inclusion into the ambit of the common law of territory within England had to have been a contributing factor in the expansion of litigation in the court of common pleas in the latter part of the sixteenth century.

The Unification of Wales with England

At the same time as Henry VIII through Parliament resumed English liberties, he likewise passed through Parliament a statute to administer law and justice in Wales as it was administered in England (Statute 27 Henry VIII, c. 26.) That statute directly united Monmouthshire into England; enrollments in the plea rolls of the court of common pleas could be entered with Monmouthshire marginations: it was henceforth treated completely as other English counties. Litigation deriving from the other Welsh counties did not appear with those counties' marginations, but the Welsh sued and were sued easily in the court of common pleas nonetheless, mostly but not only in suits carrying fictitious London marginations. Such suits began at a low level in the latter half of the fifteenth century, but were not well regarded: there was no process for actually letting defendants know that they were being sued. Such suits were regularized by the process of proclamation (see Wales,) and became increasingly frequent in the sixteenth century.

By 1607 the court of common pleas at Westminster was either as important or far more important for the Welsh counties as were their own county courts. The county courts of Wales had the same jurisdiction as the court of common pleas had in England. In the Trinity term of 1607, however, the court of common pleas entertained litigation against defendants in all the Welsh counties. The number of Welsh defendants in the court of common pleas was either as great or up to four times more than the defendants in the respective Welsh county court. Brooks recognized the possibility of purported London defendants being actually residents elsewhere, that "elsewhere" being designated in the second listing of the defendant's name. He corrected his figures for defendant's residence when the second listing provided an English residence (Brooks, pp. 64-5), but not when the second (and true) listing was to a Welsh location. Seemingly, he refrained from that correction because at that time it seemed clear (incorrectly, but I would then have agreed with him) that process could not issue against a Welsh resident. In enrollments of exigents, the margination for Welsh counties appears explicitly for the proclamation order.

The unification of Wales to England and the process of proclamation that allowed the Welsh to be sued in the court of common pleas meant that an additional thirteen counties were included within the ambit of the court of common pleas.

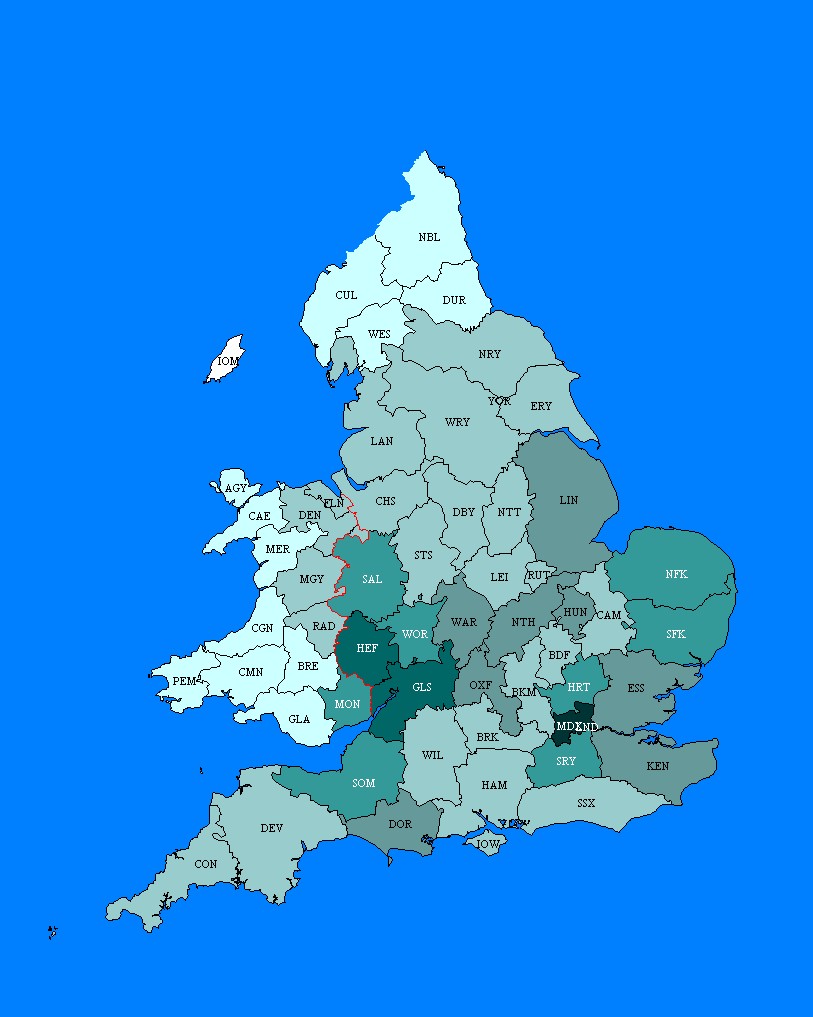

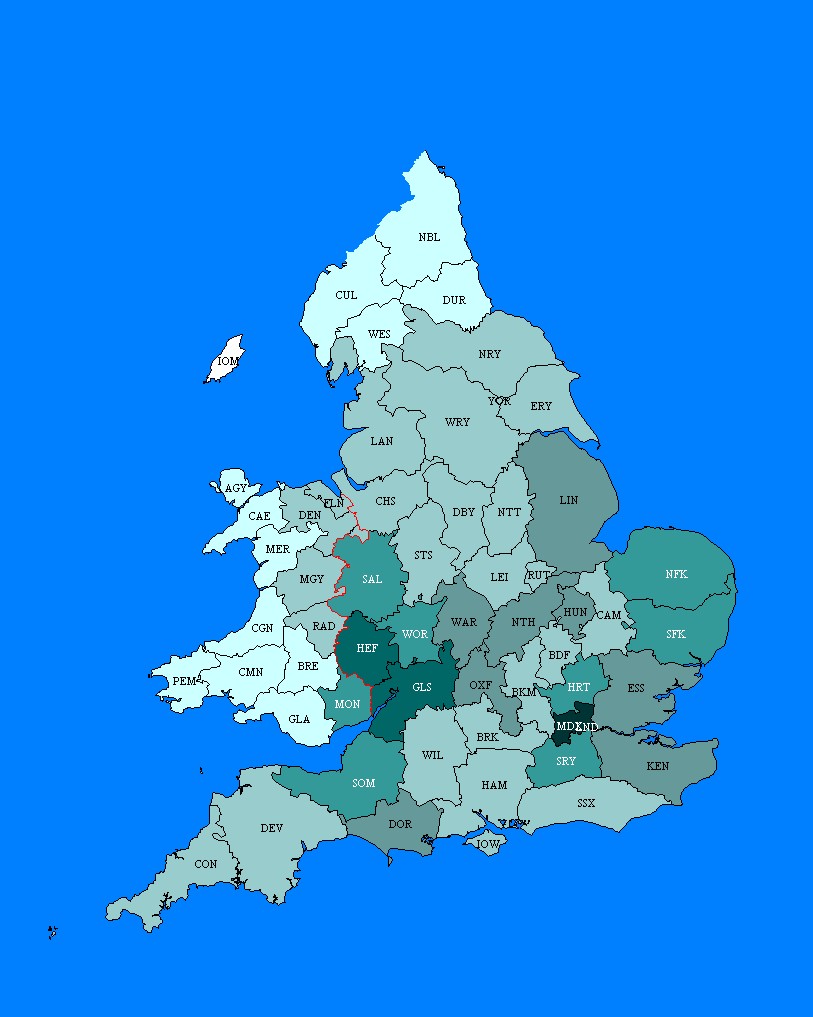

The relevant question, then, is the degree to which the inclusion of so much territory in fact influenced the increase in litigation over the course of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, that is, while the population got used to litigating in the court of common pleas and while attorneys became available to the populace for that purpose. The enrollments in the court of common pleas do list the residence of defendants. The database I have assembled from Trinity 1607 thus provides an opportunity to map out the number of defendants from each county at that time for all cases pending. (The text continues after the map.)

The calibrations on this map are rough and only indicate where the counties fall on the spectrum; moreover, the figures were adjusted by county area. The map indicates that the major areas of litigiousness were actually around London and Bristol, with a strong concentration along the Welsh border, but not actually in Wales. Most Welsh counties were not extraordinarily involved in litigation. Thus, while the inclusion of Wales within the ambit of the common law was certainly a significant factor in the increase in litigation, it would not be the most important factor. The most important factor would have to have involved the more populous and litigious areas of England itself.

As an important but tangential conclusion, the map makes it clear that no history of English law from the sixteenth century onwards can be solely about England. Any realistic history must also include Wales as a complete participant in English law.

*The Welsh county court rolls used in this study: Anglesey (National Library of Wales, GS 16/3, from 1620 [the closest surviving roll to 1607]); Brecon (GS 17/16, 17 (1607)); Caernarvon (GS20/18 (1609)); Carmarthen (GS19/49 (1607)); Denbigh (GS 21/111 (1607)); Flint (GS 30/157 (1607)); Glamorgan (GS 22/120 (1607)); Merioneth (GS23/17 (1607)); Radnor (GS 26/115, 116 (1607)); Montgomery (GS24/12 (1607)); Pembroke (GS 25/90 (1607)).